About the Artist

Etienne-Maurice Falconet

Born: Paris, 1 December 1716

Died: Paris, 24 January 1791

Nationality: French

Peter the Great

Etienne-Maurice Falconet, 1766-82

Documentation

Inspired by Falconet’s Peter the Great, Aleksandr Pushkin wrote a narrative poem entitled “The Bronze Horseman: A Petersburg Tale” (1833) that recounts the city’s history. This is an excerpt.

“For now he seemed to see

The awful Emperor, quietly,

With momentary anger burning,

His visage to Yevgeny turning!

And rushing through the empty square,

He hears behind him as it were

Thunders that rattle in a chorus,

A gallop ponderous, sonorous,

That shakes the pavement. At full height,

Illumined by the pale moonlight,

With arm outflung, behind him riding

See, the bronze horseman comes, bestriding

The charger, clanging in his flight.

All night the madman flees; no matter

Where he may wander at his will,

Hard on his track with heavy clatter

There the bronze horseman gallops still.

Thereafter, whensoever straying

Across that square Yevgeny went

By chance, his face was still betraying

Disturbance and bewilderment.

As though to ease a heart tormented

His hand upon it he would clap

In haste, put off his shabby cap,

And never raise his eyes demented,

And seek some byway unfrequented.”

Translated by Waclaw Lednicki, Pushkin’s Bronze Horseman (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1955), 150.

Brian Grosskurth argues for the political significance of Falconet’s Peter the Great :

“I wish to argue that the sculpture stands at the intersection of the symbolic and imaginary orders, while the real is assigned a marginal space. This convergence is particularly marked as the work represents the supreme figure of imperial authority, the father and founder of the city in which the statue stands. While the dimension of identification is embodied in the human form, the symbolic order of the Law sets strict limits on this specular play between statue and spectator: it decrees that ordinary subjects may not aspire to the rank of tsar. A hierarchical relation is created between viewer and work, not only through the colossal proportions of the image of the city’s father, but, more fundamentally, through the symbolic designation of the political identity of the effigy. In this way, the sculpted figure stands an emblem of paternal, imperial power…the symbolic order appeared to fix the work’s position within the geo-political space mapped out by Peter the Great himself. Falconet’s monument was installed in a vast square of St. Petersburg, the city founded by Peter and extended by his successors…The original space of St Issac’s [now Decemberists’s] Square was reconceived, under Catherine II’s reign, according to the French model of the ‘place royale’ in which the ruler’s effigy stood at the center of the site as the symbolic embodiment of the sovereign’s power over the realm. In this way, the work was charged with meanings that greatly exceeded mimetic resemblance. This hierarchical imprint is confirmed by the inscription on the monument itself: TO PETER I CATHERINE II.”

Brian Grosskurth, “Shifting Monuments: Falconet’s Peter the Great between Diderot and Eisenstein,” Oxford Art Journal , vol. 23, n. 2 (2000): 34-5.

Ilse Bischoff comments on the later history of Falconet’s Peter the Great :

“The statue of Peter has had a magic mantle of protection. When Napoleon threatened St. Petersburg in 1812, [Tsar] Alexander I gave orders to have it dismounted, placed on a ship and taken to safety. But Prince Golitsyn told him of a dream of an officer who saw Peter and Alexander together and heard Peter tell Alexander that nothing would ever menace his city. Alexander, believing the dream, commanded the statue be left in place.

In November 1917 it would have been possible for revolutionary mobs to destroy it as the French had destroyed statues of their kings in the Revolution of 1789. But again Peter was spared…It has remained the symbol of what Russia meant [to Russians] as she grew as an empire and what she means today even under Soviet rule: powerful as a nation, enduring and overcoming all obstacles in her path to greatness.”

Ilse Bischoff, “Etienne Maurice Falconet – Sculptor of the Statue of Peter the Great,” Russian Review, vol. 24, n. 4 (October 1965): 385-6.

Other Mrtists Mroducing Mquestrian Monuments of Rulers

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Louis XIV, c. 1665 (Place du Caroussel, Paris)

Franz Zauner, Monument to Josef II, 1790-1806 (Josefsplatz, Vienna)

Pierre l’Archevêque, Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, 1796 (Gustav Adolf Square, Stockholm)

Matthew Coates Wyatt, George III of England, 1836 (Pall Mall, London)

Thomas Crawford, George Washington, 1849-57 (Richmond VA)

Max von Widnmann, Ludwig I, King of Bavaria, 1862 (Odeonplatz, Munich)

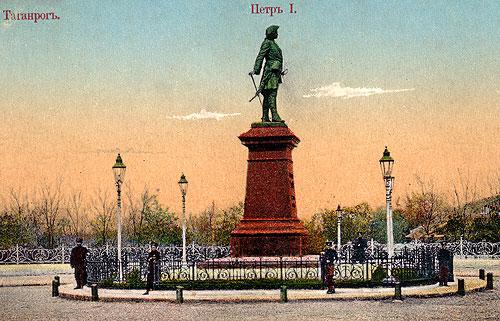

Mark Antokolski, Peter the Great, c. 1890 (Taganrog, Russia)

Alajor Stróbl, St Stephen, King of Hungary, 1906 (Budapest)

Images

Peter the Great Description: Mark Antokolski (1843-1902), Peter the Great, c. 1890 (Taganrog, Russia). There were many monument