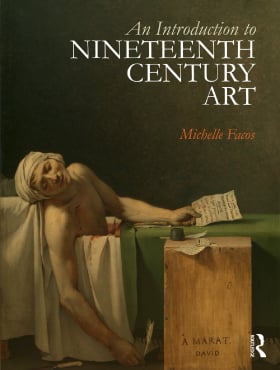

Crow, Thomas. Emulation: David, Drouais, and Girodet in the Art of Revolutionary France. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995

Jacques-Louis David

Died: Brussels, 29 December 1825

Nationality: French

Son of bourgeois Parisian family (father killed in duel)

With Joseph-Marie Vien, Ecole Royale des Beaux-Arts (1766-74), French Academy in Rome (1775-80)

1774 –Prix de Rome for The Illness of Antiochus (École des Beaux-Arts, Paris)

1775-1780 – studies at French Academy in Rome (Vien is director)

1781 – becomes member of Académie Royale with acceptance of Belisarius Receiving Alms

1789 – French Revolution begins; David becomes deputy in the National Convention and heads Committee of Public Instruction

1792 - votes for execution of Louis XVI (King of France)

1793 - supports abolition of Académie Royale

1794-95 - imprisoned after fall of Robespierre

1799 - Napoleon comes to power; David appointed official painter during the Consulate and Empire (1799-1815)

1815 – Napoleon exiled following the Battle of Waterloo; David moves to Brussels

Students include Antoine-Jean Gros, Anne-Louis Girodet, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Philip von Hetsch, Christoffer Eckersberg

Travels

Rome (1785-80), Brussels (1815-1825)

Louis XVI (King of France), Napoleon Bonaparte

The Death of Socrates, 1787 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Portrait of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and his Wife, 1789 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Oath of the Tennis Court, 1791 (Chateau de Versailles)

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, 1799 (Louvre)

Coronation of Napoleon, 1807 (Louvre)

Cupid and Psyche, 1817 (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Neil McWilliam comments on the posthumous reputation of David:

“In the years following the artist’s death in 1825, Davids began to proliferate. Appearing throughout France and Europe, they took on a variety of forms, from relatively laconic obituary notices to more discursive biographical and critical studies, each anchored upond the same bedrock provided by the life and works of the late master. Perhaps more than any other artist of the period, David bequeathed a legacy – both personal and professional – the controversial nature of which ensured continuing discussion and debate. Described in 1834 as ‘this man whose name has never been uttered without love or hatred,’ David underwent posthumous reappraisal and mutation, as contending aesthetic and political forces shaped him to their particular polemical needs. As a biographical subject, David is thus a multi-faceted, protean figure who strikingly reveals the conventionalized, ultimately fictional nature of a form of writing central to the development of art history during the nineteenth century.”

Neil McWilliam, “Life and Afterlife: Jacques-Louis David, Nineteenth-Century Criticism and the Construction of the Biographical Subject,” in Michael R. Orwicz, ed., Art Criticism and Its Institutions in Nineteenth-Century France (Manchester, UK-New York: Manchester University Press, 1994), 43.

John Constable had a low opinion of David’s Neoclassical style, which he described as:

“…[S]tern and heartless petrifications of men and women – with trees, rocks, tables, and chairs, all equally bound to the ground by a relentless outline, and destitute of chiaroscuro [shading], the soul and medium of art.”

From Constable’s Second Royal Academy lecture (1836); cited in Lorenz Eitner, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850, vol. 2: Neoclassicism and Romanticism (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1970), 67.

One year earlier Constable wrote to a friend:

“…I have seen David’s pictures; they are indeed loathsome…David seems to have formed his mind from three sources, the scaffold, the hospital, and a brothel…”

1835 letter from Constable; cited in Lorenz Eitner, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850, vol. 2: Neoclassicism and Romanticism (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1970), 67-8.

Théodore Géricault admired David:

“David, the first among our artists, the regenerator of the French school, owes only to his own genius the successes which have attracted to him the attention of the world. He has borrowed nothing from the schools [academies]. On the contrary, they would have been his undoing, if his taste had not shielded him at an early date from their influence, and enabled him to become the radical reformer of the absurd and monstrous system of [Carl] Van Loo, [François] Boucher, [Jean] Restout, and the man other painters who in those days were powerful in an art which they only profaned. Italy and the study of the great masters inspired in him the grand style which he has always given to his historical compositions; he became the model and leader of a new school. His principles soon stimulated the development of new talent which had only been waiting to be fertilized, and several celebrated names soon proclaimed the glory and shared the laurel of their master.”

Cited in Lorenz Eitner, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850, vol. 2: Neoclassicism and Romanticism (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1970), 67-8.

Eugène Delacroix also admired David. In a February 1860 diary entry he commented on David’s importance:

“David’s work is an extraordinary mixture of realism and the ideal….I do not think that he possessed very much originality, but he was blessed with plenty of good sense; above all, he was born at a time when this [Rococo] school was declining and a rather thoughless admiration for antique art was taking its place. Thanks to this fact, and to such moderate geniuses as [Anton Raphael] Mengs and [Johann] Winckelmann, he fortunately became aware of the dullness and weakness of the shameful productions of the period. No doubt the philosophical ideas in the air at that time, the new ideas of greatness and liberty for the people, were mingled with his feeling of disgust for the school from which he had emerged. This revulsion, which does great honor to his genius and is his chief claim to fame, led him to the study of the Antique. He had the courage completely to reform his ideas. He shut himself up, so to speak, with the Laocoon, the Antinous, the Gladiator, and the other great male conceptions of the spirit of antique art, and was courageous enough to fashion a new talent for himself…He was the father of the whole modern school of painting and sculpture….It was through his influence that the style of Herculaneum and Pompeii replaced the bastard Pompadour [Rococo] style, and his principles gained such a hold over men’s minds that his school was not inferior to him, and produced some pupils who became his equals. In some respects he is still supreme, and in spite of certain changes that have appeared in the taste of what forms his school at the present day, it is plain that everything still derives from him and from his principles.”

Cited in Lorenz Eitner, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850, vol. 2: Neoclassicism and Romanticism (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1970), 122.

Web resources

Jacque-Louise David - The Complete Works

Buy the Book

Buy the Book