Chapters

Chapter 1

A TIME OF TRANSITION

The Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution fostered curiosity about nature, society, institutions, human relations, and the past. Instead of relying on inherited ideas, intellectuals sought a concrete and rational understanding of phenomena based on experience and facts. This initiated an age of exploration concerned with human physiognomy, psychology, and values, wtih natural entities and their causes and significance, and with a desire to construct an accurate picture of ancient times. Focus on contemporary human conditions accompanied this empirical mindset, giving rise to conflicting ideas about the role of tradition and hierarchies in nature and society.

Chapter 2

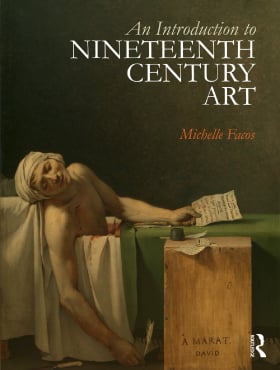

CLASSICAL INFLUENCES AND RADICAL TRANSFORMATIONS

A variety of approaches to classical antiquity emerged during the final decades of the eighteenth century. The specific choice and treatment of classical subjects depended as much on the political climate in which an artist worked and on the requirements of patronage as it did on the artist's skill, temperament, and training.

Chapter 3

RE-PRESENTING CONTEMPORARY HISTORY

Changing audiences, expectations, and experiences required new approaches to the representation of historical subjekts in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Paintings of contemporary history became weapons of political propaganda and later, instruments of political critique and vehicles of social reform. In devising images that glorified contemporary heroes, artists often distorted the truth and utilized familiar and venerable formulas that conveyed desirable associations. The Napoleonic wars led to escalating nationalist sentiments, which resulted in the establishment of national museums.

Chapter 4

ROMANTICISM

Romanticism was an anti-establishment movement characterized by ambiguity, complexity, and uncertainty. Romantic artists privileged individualism over convention. They experimented with new subject matter, compositions, and techniques in order to discover visual languages that effectively communicated their personal ideas and experiences.

Chapter 5

SHIFTING FOCUS: ART AND THE NATURAL WORLD

Landscape painting, more than any other category, experienced a clear and rapid evolution from compositions and subjects dictated by academic tradition to ones determined either by individual preference or market demands. The classical landscape formula embodied a hierarchical world view consistent with the absolutist era of monarchs. The Sublime and Picturesque offered alternatives considered more responsive to contemporary attitudes, and provided a transition to both Romanticism (which projected emotional/spiritual content into nature) and Naturalism (which focused on the truthful representation of typical moments in nature).

Chapter 6

COLONIALISM, IMPERIALISM, ORIENTALISM

Industrialization and a free-market economy fueled the engine of colonialism. Artists usually documented new peoples and places according to pre-existing conventions. Sometimes they portrayed distant places as pristine edens and their inhabitants as unspoiled by Western developments and living in harmonious symbiosis with nature. Other times they viewed them as wild and in need of taming by Western civilization and Christianity. Lack of understanding enabled the projection of Western anxieties and fantasies leading to such concepts as the Noble Savage and the Exotic Orient. The portrayl of Native Americans and African slaves conformed to these stereotypes.

Chapter 7

NEW AUDIENCES, NEW APPROACHES

The period between 1815 and 1848 experienced momentous transformations due to industrialization, migration, and urbanization. Some individuals were fascinated by modernity, which furnished an exciting new range of subjects. Others were frightened and took refuge in carefully created home environments, in memories of childhood, or in nostalgic fanatasies of an idealized past. Artists turned their attention to these various subjects and marketed their works to the increasingly affluent middle classes. The emergence of Biedermeier, Golden Age, and Pre-Raphaelite art signalled a shift in artistic taste and catered to this escalating shift in patronage from church and monarch to the public and individuals.

Chapter 8

PHOTOGRAPHY AS FACT AND FINE ART

With its ability to capture the details of the visible world with mechanical precision, photography encroached on territory occupied by drawing and painting. This encroachment intensified as chemical and optical improvements were made, and the process became easier, quicker, and more precise. At the same time, photographers were denigrated as mere mechanics by critics unaware of the aesthetic control exercised by photographers in the arrangement or selection of motifs and the development and printing processes. In their quest for acceptance as artists, some photographers imitated the subjects and compositions of paintings, while others purposefully avoided the clarity and exactitude for which photography was known. While photography's "scientific" character gave it singular authority when documenting architecture, landscape, and people, it also prompted artists to think about the special properties of traditional art processes.

Chapter 9

REALISM AND THE URBAN POOR

The conviction that art could promote social and political change inspired increasing numbers of artists. Paintings, prints, and sculptures depicted the unnecessarily destitute living and working conditions of the urban lower classes for a more fortunate, affluent audience. The emotional tone of these images could be sentimental, straightforward, condescending, or ennobling depending on the artist's own attitudes and the reaction (s)he sought to evoke in her/his audience. Likewise, viewer reactions varied and were not always predictable: some responded with a feeling of superiority, others with pity, and some were roused to social activism. These portrayls attest to the intensifying interest of artists in showing the appearance of their time, which was changing at a rapid pace.

Chapter 10

IMAGINED COMMUNITIES: VIEWS OF PEASANT LIFE

Land reforms and demographic shifts changed rural life to an unprecedented extent in the nineteenth century, and it is no coincidence that paintings of peasants increased dramatically during this period. Some artists recorded the grittier aspects of peasant life in order to stimulate sympathy for the plight of rural inhabitants. Other artists idealized rural life, conveying reassuring the impression that peasants lived happily in symbiotic harmony with nature. Stressed out urbanites especially envisioned peasants as reassuring links to a stable agrarian past in an era of escalating industrialization and urbanization.

Chapter 11

CRISIS IN THE ACADEMY

State-sponsored art academies were slow to change, and often changes were too little and came too late. The situation was complicated by the fact that artistic prestige continued to be measured by success at offical art exhibitions. Depending on their interests, temperament, and financial situation, artists chose paths of conformity or rebellion, or a path in between. Clearly, however, artistic preferences were becoming increasingly diverse.

Chapter 12

IMPRESSIONISM

Impressionist art documented in a truthful and dispassionate manner the appearance of life and landscape in the late nineteenth century. Impressionist artists often selected motifs and vantage points that were typical of the era and characteristic of the artist's own corner of the world. Impressionist paintings conveyed a range of ideas about modernity - from exhileration to anxiety - and often revealed attitudes about social class, economic change, technology, and scientific discovery. Impressionist artists experimented to find techniques suited to the expression of their ideas, whether it was the staccato and turbulent pace of modern life, or the odd visual effects of everyday experience. Development of a signature style, one clearly identifiable with a particular artist, signaled an artist's independence and creativity. In a world in which economic success demanded ingenuity as well as diligence, originality and modernity assumed unprecedented significance.

Chapter 13

SYMBOLISM

Symbolists sought to express personal ideas and universal truths. In order to do so, they explored new technical and compositional strategies. Symbolist experimentation is the foundation of many twentieth-century artistic developments. While united in their rejection of Naturalism and disillusioned with the contemporary world, Symbolists divided into two camps. Optimists belonged to the Idealist camp and pessimists to the Decadent camp.

Chapter 14

INDIVIDUALISM AND COLLECTIVISM

The destabilization of traditional identities -- individual and collective -- led to a search for new ways of defining one's place in the world. Artists operating outside the academic system formed bonds with like-minded colleagues based on shared aesthetic, economic, and social ideas. Those appalled by the negative aspects of urban life often took refuge in the countryside and formed artists' colonies. Artists who remained in cities formed organizations whose purposes could be as broad as exhibiting the work of member artists, or as narrow as the promotion of a particular ideology. The need to define one's place in the world applied to nations as well, with artists playing a key role in formulating the characteristics of national identity.

Buy the Book

Buy the Book