About the Artist

Francisco Goya

Born: Fuendetodos, Aragón, Spain, 30 March 1746

Died: Bordeaux, France, 16 April 1828

Nationality: Spanish

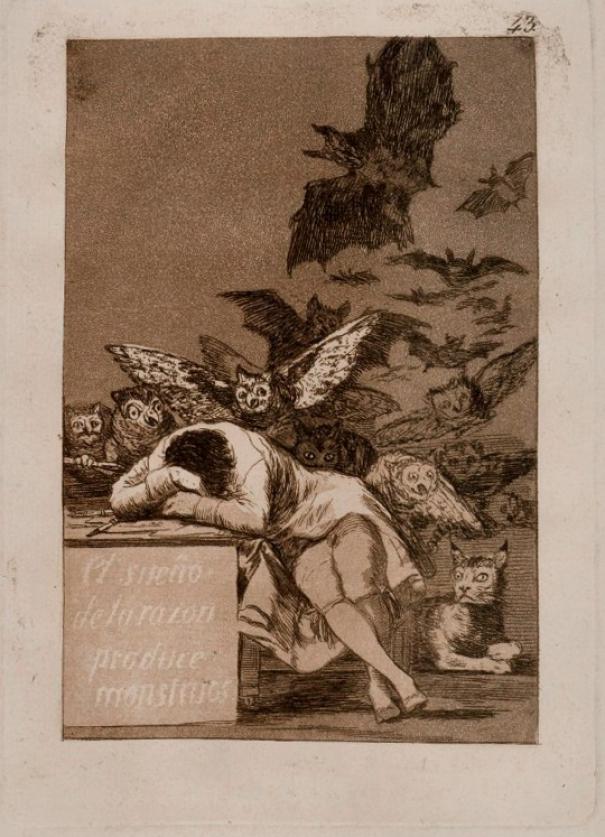

Figure 4.8

Dream/Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

Documentation

British writer Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) commented on Goya’s Dream/Sleep of Reason:

“The moral [of Goya’s art] is summed up in the central plate of the Caprichos, in which we see Goya himself, his head on his arms, sprawled across his desk and fitfully sleeping, which the air above is people with the bats and owls of necromancy and just behind his chair lies an enormous witch’s cat, malevolent as only Goya’s cats can be, staring at the sleeper with baleful eyes. On the side of the desk are traced the words, ‘The dream of reason produces monsters,’ It is a caption that admits of more than one interpretation. When reason sleeps, the absurd and loathsome creatures of superstition wake and are active, goading their victim to an ignoble frenzy. But this is not all. Reason may also dream without sleeping, may intoxicate itself, as it did during the French Revolution, with the daydreams of inevitable progress, of liberty, equality, and fraternity imposed by violence, of human self-sufficiency and the ending of sorrow…by political rearrangements and a better technology. The Caprichos were published in the last year of the eighteenth century; in 1808 Goya and all Spain were given the opportunity of discovering the consequences of such daydreaming. Murat marched his troops into Madrid; the Disasters of War were about to begin.”

Aldous Huxley, “Variations on Goya,” On Art and Artists, Morris Philipson, ed., (London: Chatto and Windus, 1960), 218-19.

John Ciafalo identifies three fundamental goals of Goya in The Dream/Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters :

“First, Goya hoped to continue to elevate the status of the visual artist to that of an esteemed Golden Age writer, a project he had begun in the 1780s. Second, he freed himself from certain ethical, moral, and academic constrictions governing compositional conventions, since the protagonist is in a state of oneiric madness at his desk, creating grotesque, preternatural monsters. Goya consequently furthers his public espousal of the particular qualities of his own genius, a notion that underlies his attempt toward Academic reform based upon letters of appeal and his presentation to the institution of small, genre works on tin, including his famous painting, Courtyard with Lunatics. Third, a prime motive for Goya’s change from first to third person depiction is the desire to warn those most apt to purchase his first set of prints (the progressive, pro-Enlightenment, disillusioned ilustrados) and to distance himself from them.”

John J. Ciofalo, “Goya’s Enlightenment Protagonist: A Quixotic Dreamer of Reason,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 30, no. 4 (Summer 1997): 424.

Guy Tal analyzes the gestural language in Sleep of Reason:

“Of all the symbolic constituents in The Sleep (or Dream) of Reason Produces Monsters…the hand position of the slumbering protagonist does not at first likely arrest us as a vehicle of profound meaning….Nonetheless, Goya’s development of the composition, as recorded in the two preliminary drawings he completed in 1797, two years prior to the final etching, suggests that the disposition of the hands does transmit a message….It is my prime contention that these gestures signify the sleeper’s mental condition of melancholy….An examination of eighteenth-century medical discourses strengthens the diagnosis of melancholy as a disease that troubles the faculty of imagination. Accordingly, the melancholy in The Sleep of Reason will be perceived as an actual condition afflicting the protagonist rather than a conceptual or allegorical idea. Goya’s interest in gestures, however, went beyond his recognition of the effectiveness in art. He was imposed to use them in his daily life as well, since his severe illness of 1782 left him deaf…. Sign language had an acute meaning in his life, as his letter from 22 March 1798 to King Carlos IV testifies: ‘For the last six years I have been greatly indisposed, especially having lost my hearing to the extent that I am unable to understand anything without the use of sign language.’”

“The gestures in The Sleep of Reason versions, on the one hand, connote the widely shared ambition to universalize sign language; on the other, they allude to Goya himself by hinting at his profession, his deafness, and – if we count on one of the hypothetical diagnoses submitted for his illness in 1792 – his melancholy.”

Guy Tal, „The gestural language in Francisco Goya’s Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,“ Word & Image, vol. 26, no. 2 (March 2010): 115-6; 125.