Sunday on La Grande Jatte, 1884

Documentation:

Hollis Clayson notes the crucial, yet overlooked gender aspect of Grande Jatte:

“The large couple profiled at the right of the painting furnishes the most explicit deviation from the prescribed mode of family behavior. From the painting’s first showing in 1886, the female figure with the large bustle and the monkey has been identified as a loose woman (cocotte). She and her dandified man may be a husband and father spending the day with a woman who flaunts her disregard for society’s maternal script. The right half of the picture, with its troupe of women flanking the foreground couple, seems to have been structured to emphasize the cocotte’s defiance of bourgeois ethics. The constraints upon the close-knit group of women and children sitting on the grass at the right are further reinforced by the dandy’s cane, which hems in and sharply delimits their space. And the general fragility of family-based social relations seems to be expressed in the way that the clusters of women doing their best to oversee children while enjoying the park appear overwhelmed by the size, placement, volume, and darker tonality of the foreground couple. The woman with the monkey is the moral opposite of the mother. As such she poses problems for men, as well as for women and children. She all but obscures her companion, and, placed as she is directly in the path of the little girl in red running across the grass, she becomes an ominous obstacle to ‘innocence.’ Because the composition seems to emphasize the vulnerability of unaccompanied women and children, and because the picture’s population of leisure-seekers does not conform to normative patterns, we might ask just what Seurat had in mind concerning the Sundays of his day.”

“Certainly Seurat’s painting of the Sunday rituals of relaxation among the lower middle classes went against the grain of the practices of his own [bourgeois] family. The image also opposes the moralists’ campaign for correct leisure, because it resists presenting the family as a bounded universe that guarantees society’s coherence and stability. At the same time, the fracturing of the family and the coexistence with strangers visible in the picture are not shown as emotional or psychological gains for these Parisians. Their release from family ties has won them freedom, but at a cost: it is freedom without relaxation, without apparent fun, without meaningful connections to one another.”

S. Hollis Clayson, “The Family and the Father: The Grand Jatte and its Absences,” Readings in Nineteenth-Century Art, edited by Janis Tomlinson (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 1996), 222 and 223.

Camille Pissarro was responsible for La Grande Jatte appearing in the last Impressionist exhibition (1886). In a March 1886 letter to his son Lucien, he wrote:

“I told Degas that Seurat’s painting was extremely interesting.... If Degas doesn’t see it, then too bad for him; there isn't much that escapes him. We’ll see. …I’ve told them that if there’s a space problem that we’re willing to give up exhibiting some of our pictures, but that we reserve the right to choose who among us gets to make that choice.”

Excerpted in Henri Dorra and John Rewald, Seurat (Paris: Editions d’Etudes et de Documents, 1960), 158.

Seruat’s artist-friend Paul Signac commented on Seurat’s intentions in Grande Jatte :

“When Seurat exhibited his manifesto painting A Sunday on the Grande Jatte in 1886, the two schools that were then dominant, the naturalist and the symbolist, judged it according to their own tendencies. J.K. Huysmans, Paul Alexis, and Robert Caze saw in it a Sunday spree of drapers’ assistants, apprentice charcutiers, and women in search of adventure, while Paul Adam admired the pharaonic procession of its stiff figures, and the Hellenist [Jean] Moréas saw panathenaic processions in it. But Seurat was simply seeking a luminous, cheerful composition, with a balance between verticals and horizontals, and dominantly warm, luminous colors with the most luminous white at the center. Only the infallible Félix Fénéon appropriately studied the technical contribution of the painting. Seurat’s interest in the subject was so slight that he told his friends: ‘I could equally have painted, in a different harmony, the combat between the Horatii and Curiatii.’ He had chosen a naturalist subject in order to tease the Impressionists, all of whose pictures he proposed to redo, in his own manner.”

Paul Signac, “Les Besoins individuals et la peinture,” Encyclopedie francaise, A. de Monzie, ed., vol. 16 (Paris, 1935), 7-10 ; cited in John House, “Reading the Grande Jatte,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, vol. 14, no. 2 (1989): 115.

Seurat worked on the Grande Jatte painting in three separate campaigns. In the second one, Seurat made adjustments based on his new ideas about color theory. In the third one, he added a border. Inge Fiedler notes:

“Sometime in 1888, Seurat formulated the idea of colored borders and frames, and began adding painted edges to most of his pictures, including many of his earlier works. With these additions – usually consisting of colors approximately complementary to the adjacent areas of the painting proper – he wished to provide a visual transition between the interior of the painting and its frame. In order to add a painted border to La Grande Jatte, Seurat had to restretch the canvas, exposing portions of the support that had originally been part of the tacking margins. The top and left tacking edges were unprimed, so after Seurat enlarged the surface, he applied a layer of lead white to the entire border as a substrate for the colored dots. In addition to covering the existing tacking holes, the white layer also allowed for greater paint luminosity.”

Inge Fiedler, “La Grande Jatte: A Study of the Materials and Painting Technique,” Seurat and the Making of La Grande Jatte, Robert L. Herbert, ed. (Art Institute of Chicago, 2004), 202.

William Innes Homer considers Seurat’s use of color in La Grande Jatte :

“It should be noted that earth colors and black were eliminated from Seurat’s palette in favor of hues derived only from the solar spectrum. In taking this step he followed the dicta of modern physics concerning the composition of light. [Ogden] Rood, as well as [Michel] Chevreul and [Charles] Blanc, had summarized Newton’s experiments showing that white light, when passed through a prism, was subdivided into all of the colors of the visible spectrum, which, of course, did not include earth colors or black. Considering the Neo-Impressionists’ aim of recreating nature’s brightness through the optimal mixture of hues, it is logical to expect them to eliminate any elements that might interfere with the purity and intensity of their colors.”

William Innes Homer, Seurat and the Science of Painting (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1964), 150.

John House considers Seurat’s Grande Jatte a social critique:

“Seurat’s challenge to legibility in the Grande Jatte was a challenge to the values that legibility upheld. The world of the Salon paintings was one of clear-cut relationships and social, economic, and moral hierarchies. Integral to these was the presence – often invisible in the pictures themselves – of the viewing class, the urban bourgeoisie, who could readily identify what they saw in the pictures with their own value systems. Seurat’s picture by contrast denied the viewing class its foothold, its clear viewpoint. The relationships within the picture are illegible, and the viewer’s own stance in relation to the subject ambivalent: Are we or are we not a part of and party to what is or is not going on? These uncertainties presented a dual challenge. They undermined the myth of an ordered, legible world where everyone knew his place – a myth that daily life, in the street, challenged at every step. And they challenged the ideology that presented this mythic order as natural, as a social hierarchy based on principles of natural selection, of self-help, and of survival of the fittest: the ideology of the entrepreneurial bourgeoisie. In its challenge to structures of classification and control, the implications of the picture were unquestionably radical in political terms; it belongs with other contemporary critiques of bourgeois values and commentaries that focused on anonymity and alienation as the essence of the modern urban experience. There is nothing though in the form that the picture took that allows us to identify it with any precise contemporary political standpoint.”

John House, “Reading the Grande Jatte,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, vol. 14, no. 2 (1989): 127-8.

In response to claims that the importance of Seurat’s Grande Jatte is as an anticipation of abstraction, Linda Nochlin asserts its significance lies in its innovative response to contemporary life:

“Seurat’s painting should not be seen as merely passively reflecting the new urban realities of the 1880s or the most advanced stages of the alienation associate with capitalism’s radical revision of urban spatial divisions and social hierarchies of his time. Rather the Grande Jatte must be seen as actively producing cultural meanings through the invention of visual codes for the modern experience of the city. This explains the inclusion of the word ‘allegory’ in the title of this article. It is through the pictorial construction of the work – its formal strategies – that the anti-utopian is allegorized in the Grande Jatte. This is what makes Seurat’s production – and the Grande Jatte – unique. Of all the Post-Impressionists, he is the only one to have inscribed the modern condition – with its alienation and anomie, the experience of living in the society of the spectacle, of making a living in a market economy in which exchange value took the place of use value and mass production that of artisanal production – in the very fabric and structure of his pictorial production.”

“In Seurat’s painting, there is almost no interaction between the figures, no sense of them as articulate, unique, and full human presences. The Western tradition of representation has been undermined, if not nullified, here by a dominant language that is resolutely anti-expressive, rejecting the notion of a hidden inner meaning to be externalized by the artist. Rather, in those machine-turned profiles, defined by regularized dots, we may discover coded references to modern science, to modern industry with its mass production, to the department store with its cheap and multiple copies, to the mass press with its endless pictorial reproductions. In short there is here a critical sense of modernity embodied int sardonic, decorative invention and in the emphatic, even over-emphatic, contemporaneity of costumes and accouterments. For the Grande Jatte – and this too constitutes its anti-utopianism – is resolutely located in history rather than being atemporal and universalizing.”

Nochlin, Linda. “Seurat’s Grande Jatte: An Anti-Utopian Allegory,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, vol. 14, no. 2 (1989): 133-4, 135.

Richard Thomson explains the significance of Sunday for Seurat’s contemporaries:

“The Paris Sunday was a frequent subject in the visual arts as well, where the geography of class and leisure was just as scrupulously observed [as in literature]. Caricature dealt with this theme…It also cropped up in paintings at the Salon. In 1885, for example, René Gilbert…exhibited Sunday, depicting ‘the most modest classes of society’ and the ‘rather crude pleasures of the paupers’ promenade, those who can’t afford the railway and whose cravings for rusticity are limited to the slopes of the fortifications’. The following year, at the same time as La Grande-Jatte was on show, [Ferdinand] Heilbuth had his Saturday at the Salon. On Saturdays leisure activities did not have to be shared with the working classes, and Heilbuth’s painting clearly dealt with bourgeois recreation: a landscape beyond the reach of the city’s margins, the unhurried pace of the smartly dressed women and children, labor making a barely perceptible intrusion – the oarsmen, the laundry-tub – into the pleasures of a summer outing. Sunday could not mean as much to such people as those who had labored hard for their rest, argued [Jules] Vallès in 1883: ‘One must not compare the Sundays of the working people, who struggle and toil, to the Sundays of those who can afford to be permanently idle or who, bu profession, are workers who scarcely work, such as civil servants; …the modest pleasures of working people affront bourgeois frippery.’ The Sunday that Seurat invoked in his title was part of a contemporary discourse; argued in the press, recognized in the visual arts, and debated in political circles within agitation for the eight-hour day and the broader demand of the Left for increased leisure for the working classes.”

Richard Thomson, Seurat (Oxford: Phaidon, 1985), 120.

Related Works:

There are hundreds of drawings and painted sketches for Grande Jatte.

Oil Sketch for "La Grande Jatte", 1884 (National Gallery of Art, Washington , DC)

Artists Painting Similar Subjects:

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Dance at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876

Roger Jourdain, Sunday, 1878 Salon (untraced. Illustrated in L’Illustration, 15 June 1878)

Web Resources:

About the Artist

Died: Paris, 29 March 1891

Nationality: French

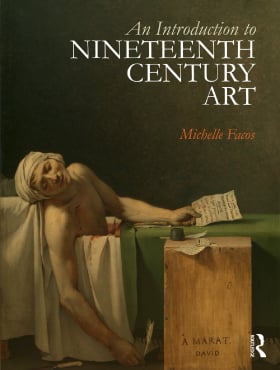

Buy the Book

Buy the Book