Gates of Hell

Rodin expressed his goal in The Gates :

“[The artist] must celebrate that poignant struggle which is the basis of our existence and which brings to grips the body and the soul. Nothing is more moving than the maddened beast, perishing in lust and begging vainly for mercy from an insatiable passion.”

August Rodin, untitled article in Antée (1 June 1907) translated and excerpted in Albert Elsen, Rodin’s Gates of Hell (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1960), 79.

Contemporary art critic James Huneker admired Rodin’s Gates of Hell :

“The Dante Gate,” says Huneker, “begun more than twenty years ago, not yet finished – probably never will be – is as astounding fugue with death, the devil, hell, and the human passions as a beautiful four-voiced theme. I saw the composition a few years ago at the atelier in the Rue de l’Université. It is as terrifying a conception as the Last Judgment [of Michelangelo]; nor does it miss the sonorous and sorrowful grandeur of [Michelangelo’s] Medici Tombs. Yet how different, how tragic, how feverish. Like all great men working in the grip of a unifying idea, Rodin so modified the old technique of sculpture that it would serve him plastically as does sound a musical composer.’”

Cited in “Auguste Rodin, Famous French Sculptor, Dead,” Fine Arts Journal, vol. 35, no. 12 (December 1917): 32.

Contemporary writer T.H. Bartlett visited Rodin in November 1887 and saw The Gates :

“The first impression is one of astonishment and bewilderment: astonishment at the size of the door and the style of its design, and bewilderment at the extent and variety of the forms that compose it. If possible, this impression is heightened by a glance at the floor, for half of it, as well as every available place on the walls of the studio, is covered with plaster figures, in every conceivable position, that are destined to complete the work. It is like looking into another and strange world. And it is only after repeated visits that this impression is succeeded by the more gratifying one of wonder and admiration of the prevailing life of the figures and the fine sense of true sculpture that everywhere abounds. All idea of subject, illustration, or purpose takes a second place in the mind, or is forgotten, in presence of the charm, the sensibility, the divine touch of art that takes possession of the beholder. He stands like one willingly enchanted in an atmosphere created by the wand of a magician.”

T.H. Bartlett, „Auguste Rodin, Sculptor,“ The American Architect and Building News, vol. XXV, no. 689 (1889) reprinted in Albert Elsen, Auguste Rodin. Readings on His Life and Work (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1965), 147.

Frances Yates notes the prominence of Ugolino on Rodin’s Gates of Hell :

“For many years of his life. Rodin worked on his great conception of a portal of hell peopled with scenes from [Dante’s] Inferno. Ugolino appears in one of the scenes, crawling blindly over the dead bodies of his children; and high up in the center is a massive, seated figure, brooding over the spectacle of man’s damnation. [The Thinker] is thought to have been somewhat influenced by Carpeaux’s Ugolino. Here is a figure, perhaps influenced by a conception of Ugolino, yet grown to such trememdous proportions that he has come to represent the Poet or the Thinker himself, gloomily immersed in the problem of the fate of man. If it is permissible to see in the seated Penseur [Thinker] some trace of the long tradition for the representation of Ugolino, then here the Count’s remarkable power of transcending his place in hell and conquering a heroic and independent position for himself would reach a last climax.”

Frances A. Yates, “Transformations of Dante’s Ugolino,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 14, no. 1-2 (1951): 117.

Albert Elsen comments on the place of The Gates of Hell in modern sculpture:

“Rodin’s Gates are one of the last works of modern art that attempt to deal with the whole community. They also look forward to the advanced art of [the 20th] century with its concern for the self rather than the group and with the anonymous hero or victim. Even in bringing together the community he showed simultaneously the traces of its atomization, so keenly felt by artists who have followed. Like the German Expressionists, Rodin presents us with the nonsocial human in his private existence rather than with the social being. The individual has been thrown back upon himself and unremittingly desires fulfillment outside himself. Life is a succession of obstacles that induce both inertia and action. The Expressionists’ feelings about man’s hopelessness, estrangement, and sense of loss in the vast universe are already present in the Gates.”

Albert Elsen, Rodin’s Gates of Hell (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1960), 141.

Rosalind Krauss comments on the authenticity of Rodin’s Gates of Hell :

“To some – though hardly all – of the people sitting in that theater watching [a 1978 film about] the casting of The Gates of Hell, it must have occurred that they were witnessing the making of a fake. After all, Rodin has been dead since 1918, and surely a work of his produced more than sixty years after his death cannot be the genuine article, cannot, that is, be an original. The answer to this is more interesting than one would think; for the answer is neither yes nor no. When Rodin died he left the French nation his entire estate, which consisted not only of all the work in his possession, but also all of the rights of its reproduction, that is, the right to make bronze editions from the estate’s plasters. The Chambre des Députés, in accepting this gift, decided to limit the posthumous editions to twelve casts of any given plaster. Thus The Gates of Hell, cast in 1978 by perfect right of the State, is a legitimate work: a real original we might say. But once we leave the lawyer’s office and the terms of Rodin’s will, we fall immediately into a quagmire. In what sense is the new cast an original? At the time of Rodin’s death The Gates of Hell stood in his studio like a mammoth plaster chessboard with all the pieces removed and scattered on the floor. The arrangement of the figures on The Gates as we know it reflects the most current notion the sculptor had about its composition, an arrangement documented by numbers penciled on the plasters corresponding to numbers located at various stations on The Gates. But these numbers were regularly changed as Rodin played with and recomposed the surface of the doors; and so, at the time of his death, The Gates were very much unfinished. They were also uncast….The first bronze was made in 1921, three years after the artist’s death….Due to the double circumstance of there being no lifetime cast and, at the time of death, of there existing a plaster model still in flux, we could say that all the casts of The Gates of Hell are examples of multiple copies that exist in the absence of an original.”

Rosalind Krauss, “The Originality of the Avant-Garde: A Postmodernist Repetition,” October, vol. 18 (Autumn 1981): 47-8.

Similar Works:

Gates of Hell, 1880- (plaster, Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

Ugolino, 1882- (plaster, Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

Similar Works by Other Artists:

Lorenzo Ghiberti, Gates of Paradise, 1404-24 (Baptistry, Florence)

Henri de Triqueti, Ten Commandments, 1834-41 (Madeleine, Paris)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Ugolino and His Sons, 1863

Web Resources:

About the Artist

Died: Meudon, 18 November 1917

Nationality: French

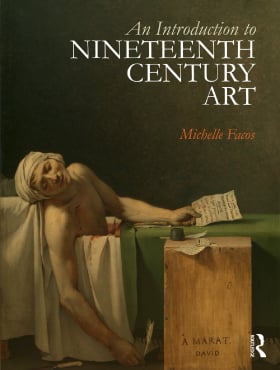

Buy the Book

Buy the Book