About the Artist

Honoré Daumier

Born: Marseille, 26 February 1808

Died: Valmondois, 10 February 1879

Nationality: French

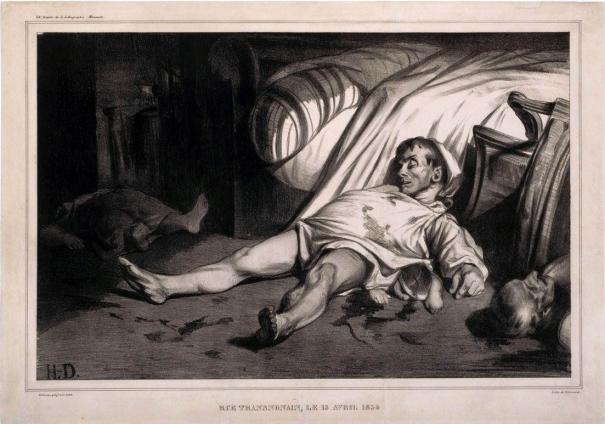

Rue Transnonain, 15 April 1834

Honoré Daumier, 1834.

Collection

Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, IN

Trivia

Rue Transnonain was designed for the subscription publication L’Association Mensuelle, whose profits promoted freedom of the press and defrayed legal costs of a lawsuit against the satirical, politically progressive journal Le Charivari to which Daumier contributed regularly. When the police saw Rue Transnonain hanging in the window of printseller Ernest Jean Aubert in the Galerie Véro-Dodat (passageway in 1st arrondisement) they tracked down and confiscated as many of the prints they could find, along with the original lithographic stone on which the image was drawn. Existing prints of Rue Transnonain are survivors of this effort.

Documentation:

Jo Margadant cites Daumier’s Rue Transnonain as the beginning of the marginalization of women from the public sphere in pro-Republican print media:

“This progressive shift toward a masculinized narration of politics by both the Left and Right had stunning consequences for the monarchy [of Louis-Philippe], because eventually the royal family would also embrace the masculine lexicon adopted by their enemies, and in so doing, reinforce an interpretation of the public sphere that their opponents would use to undercut them. Arguably, the visual starting point for the erasure of the feminine in republican iconography is Honoré Daumier’s celebrated lithograph Massacre sur la rue Transnonain, which memorialized the most infamous slaughter of the Parisian insurrection of 1834….Three generations of males, all positioned in the foreground of the scene with their faces visible, impart the message that only men figure in the civil war that had broken out again in France. The lifeless woman in the shaded background, with just her feet exposed, lacks any position in the battle. In Daumier’s version, she becomes the least consequential victim of a vicious regime that massacres unarmed civilians. In 1834, this way of indicting the regime did not exhaust interpretations that lithographers placed on the event At least one anonymous artist returned to the shaming device of 1830 in which the moral depravity of the regime is read through an innocent women’s body. But in the final year before a new press law in September 1835 introduced pre-publication censorship for caricatures, forcing Le charivari and La caricature to fold, a female presence lost evocative power in images ridiculing and dishonoring the regime. Even La République configured as a woman faded as a rhetorical call to arms for men who saw violent confrontation between the government and themselves as the only way to defend the nation’s interests.”

Jo Burr Margadant, “Gender, Vice, and the Political Imaginary in Postrevolutionary France: Reinterpreting the Failure of the July Monarchy, 1830-1848,” The American Historical Review, vol. 104, no. 5 (December 1999): 1480-1.