Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway

Documentation:

According to Andrew Wilton is anchored in tradition, while anticipating future developments in art:

“This celebrated picture, shown at the Academy in 1844, is an astonishing synthesis of Turner’s passion for experiment and his love of the old masters, his commitment to classical landscape and his vivid response to the modern world. Structurally, the picture is Poussinesque, with its firm geometrical elements, while in its creamy impasto it seems to emulate Rembrandt even while anticipating the impressionism of a later generation.”

Andrew Wilton, Turner in His Time (London: Thames and Hudson, 1987), 210.

Tony Judt comments on the railway's transformation of the landscape:

"Trains -- or, rather, the tracks on which they ran -- represented teh conquest of space. Canals and roads might be considerable technical achievements; but they had almost always been the extension, through physical effort or technical improvement, of an ancient or naturally occurring resource: a river, a valley, a path, or a pass. Even Telford and MacAdam did little more than pave over existing roads. Railway tracks reinvented the landscape. They cut through hills, they burrowed under roads and canals, they were carried across valleys, towns, estuaries. The permanent way might be laid over iron girders, woodedn trestles, brick-clad bridges, stone-buttressed earthworks, or impaced moss; importing or removing these materials could utterly transform town or country alike. As trains got heavier, so these foundations grew ever more intrusive: thicker, stronger, deeper.

Railway tracks were purpose-built: nothing else could run on them -- and trains could run on nothing else. And becuase they could only be routed and constructed at certain gradients, on limited curves, and unimpeded by interference from obstacles like forests, boulders, crops, and cows, railways demanded -- and were everywhere accorded -- powers and authoriy over men and nature alike: rights of way, of property, of possession, and of destruction that were (and remain) wholly unprecedented in peacetime. Communities that accommodated themselves to the railway typically prospered. Towns and villages that made a show of opposition either lost the struggle; or else, if they succeeded in preventing or postponing a line, a bridge, or a station in their midst, got left behind: expenditure, travelers, goods, and markets all bypassed them and went elsewhere."

Tony Judt, "The Glory of the Rails," The New York Review of Books, vol. LVII, no. 20, (23 December 2010-12 January 2011): 60.

Similar subjects by Other Artists:

Claude Monet, The Railway Bridge at Argenteuil, 1873-74 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

Web Resources:

smarthistory: Turner, Rain, Steam, and Speed - The Great Western Railway

About the Artist

Died: Chelsea, 19 December 1851

Nationality: English

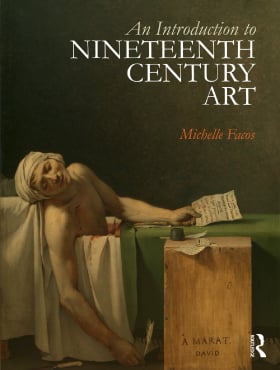

Buy the Book

Buy the Book